Xi Wangmu, the shamanic great goddess of China

Max Dashu

One of the oldest deities of China is Xi Wangmu (Hsi Wang Mu). She lives in the Kunlun mountains in the far west, at the margin of heaven and earth. In a garden hidden by high clouds, her peaches of immortality grow on a colossal Tree, only ripening once every 3000 years. The Tree is a cosmic axis that connects heaven and earth, a ladder traveled by spirits and shamans.

Xi Wang Mu controls the cosmic forces: time and space and the pivotal Great Dipper constellation. With her powers of creation and destruction, she ordains life and death, disease and healing, and determines the life spans of all living beings. The energies of new growth surround her like a cloud. She is attended by hosts of spirits and transcendentals. She presides over the dead and afterlife, and confers divine realization and immortality on spiritual seekers.

The name of the goddess is usually translated as Queen Mother of the West. Mu means “mother,” and Wang, “sovereign.” But Wangmu was not a title for royal women. It means “grandmother,” as in the Book of Changes, Hexagram 35: “One receives these boon blessings from one’s wangmu.” The classical glossary Erya says that wangmu was used as an honorific for female ancestors. [Goldin, 83] The ancient commentator Guo Pu explained that “one adds wang in order to honor them.” Another gloss says it was used to mean “great.” Paul Goldin points out that the Chinese commonly used wang “to denote spirits of any kind,” and numinous power. He makes a convincing case for translating the name of the goddess as “Spirit-Mother of the West.” [Goldin, 83-85]

The oldest reference to Xi Wangmu is an oracle bone inscription from the Shang dynasty, thirty-three centuries ago: “If we make offering to the Eastern Mother and Western Mother there will be approval.” The inscription pairs her with another female, not the male partner invented for her by medieval writers—and this pairing with a goddess of the East persisted in folk religion. Suzanne Cahill, an authority on Xi Wangmu, places her as one of several ancient “mu divinities” of the directions, “mothers” who are connected to the sun and moon, or to their paths through the heavens. She notes that the widespread tiger images on Shang bronze offerings vessels may have been associated with the western mu deity, an association of tiger and west that goes back to the neolithic. [Cahill, 12-13]

After the oracle bones, no written records of the goddess appear for a thousand years, until the “Inner Chapters” of the Zhuang Zi, circa 300 BCE. This early Taoist text casts her as a woman who attained the Tao [Feng, 125]:

Xi Wang Mu attained it and took her seat on Shao Guang mountain.

No one knows her beginning and no one knows her end.These eternal and infinite qualities remain definitive traits of the goddess throughout Chinese history.

The Shan Hai Jing

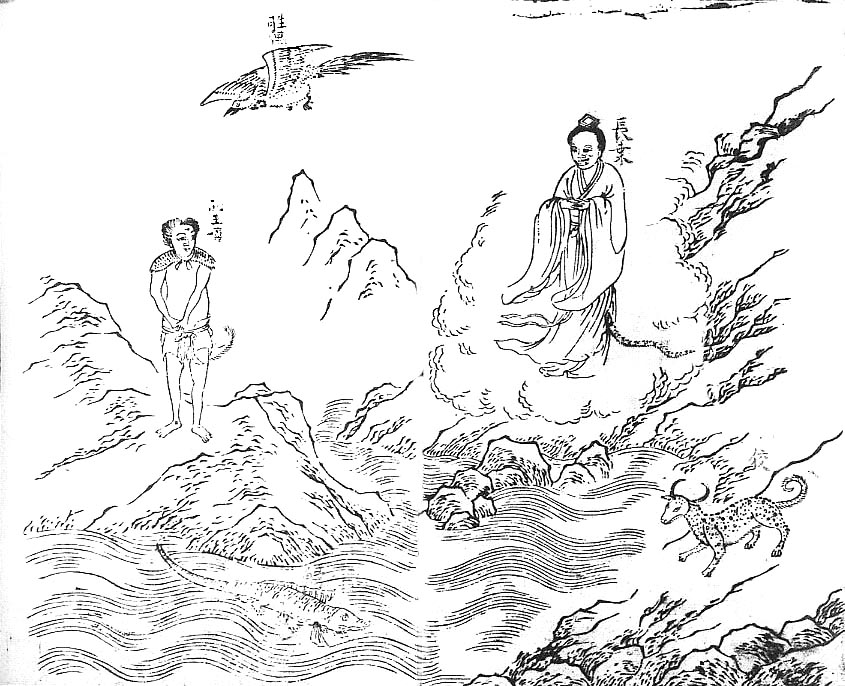

Another ancient source for Xi Wangmu is the Shan Hai Jing (“Classic of Mountains and Seas”). Its second chapter says that she lives on Jade Mountain. She resembles a human, but has tigers’ teeth and a leopard’s tail. She wears a head ornament atop her wild hair. [Remi, 100] Some scholars interpret this as a victory crown. [Birrell, 24] Most think it is the sheng headdress shown in the earliest reliefs of the goddess: a horizontal band with circles or flares at either end. [Cahill, 16; Strassberg, 109]

Xi Wangmu wearing the Sheng Crown

The sheng is usually interpreted as a symbol of the loom. The medieval Di Wang Shih Zhi connects it to “a loom mechanism” the goddess holds. Cahill says that the sheng marks Xi Wangmu as a cosmic weaver who creates and maintains the universe. She also compares its shape to ancient depictions of constellations—circles connected by lines—corresponding to the stellar powers of Xi Wangmu. She “controls immortality and the stars.” Classical sources explain the meanings of sheng as “overcoming” and “height.” [Cahill, 45; 16-18]

This sign was regarded as an auspicious symbol during the Han dynasty, and possibly earlier. People exchanged sheng tokens as gifts on stellar holidays, especially the Double Seven festival in which women’s weaving figured prominently. It was celebrated on the seventh day of the seventh month, at the seventh hour, when Xi Wangmu descended among humans. Taoists considered it the most important night of the year, “the perfect night for divine meetings and ascents.” [Cahill, 16, 167-8] It was the year’s midpoint, “when the divine and human worlds touch,” and cosmic energies were in perfect balance. [Despeux / Kohn, 31]

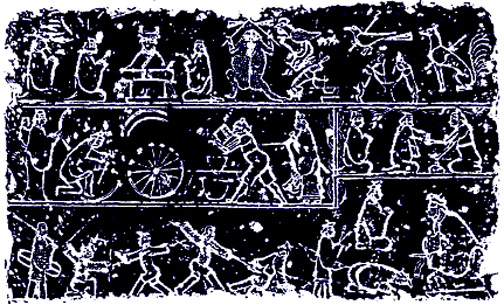

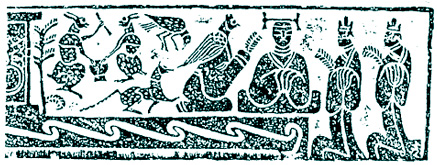

Xi Wangmu seated amidst worshippers, dancing frog, magical raven, nine-tailed fox, and various ritual scenes. Directly beneath her is a possible representaation of the celestial Grindstone.The Shan Hai Jing goes on to say of the tigress-like Xi Wangmu: “She is controller of the Grindstone and the Five Shards constellations of the heavens.” [Cahill, 16] The Grindstone is where the axial Tree connects to heaven, the “womb point” from which creation is churned out. [Mitchell cite] In other translations of this passage, she presides over “the calamities of heaven and the five punishments.” [Strassberg, 109] For Guo Pu, this line referred to potent constellations. [Remi, 102] The goddess has destructive power—she causes epidemics, for example—but she also averts them and cures diseases. [Asian Mythology]

The passage above also says that the tiger-woman on Jade Mountain “excels at whistling.” Other translators render this line as “is fond of roaring” or “is good at screaming.” The character in question, xiào, does not translate easily. It is associated with “a clear, prolonged sound” that issues from the throats of sages and shamans. (It may have resembled Tuvan throat singing.) Xiào was compared to the cry of a phoenix, a long sigh, and a zither. Its melodic sound conveyed much more than mere words, and had the power to rouse winds and call spirits. Taoist scriptures also refer to the xiào, and in the Songs of Chu it appears “as a shamanistic ritual for calling back the soul of the deceased.” [Yun, online]

The twelfth chapter of the Shan Hai Jing returns to the goddess, seated on She Wu mountain: “Xi Wangmu rests on a stool and wears an ornament on her head. She holds a staff. In the south, there are three birds from which Xi Wangmu takes her nourishment. They are found to the north of the Kunlun mountains.” [Remi, 481] The three azure birds that bring fruits to the goddess belong to her host of shamanic spirits and emissaries that turn up in art and literature.

An 18th-century woodcut depicts the goddess in her old shamanic form, with tiger’s teeth and bamboo staff, sitting on a mountaintop with various chimeric animals. From an edition of the Shan Hai Jing.

This description places Xi Wangmu on the mountain She Wu—“Snake Shaman.” Wu is the Chinese name for female shamans. Its written character depicts two dancers around a central pillar—the same cosmic ladder that recurs in the iconography of Xi Wangmu. The Songs of Chu, a primary source on ancient Chinese shamanism, describes Kunlun mountain as a column connecting heaven and earth, endlessly deep and high. [Cahill, 47] It is the road of shamanic journeys between the worlds.

Xi Wangmu has shamanic attributes in the Shan Hai Jing. She is depicted as a tigress, an animal connected to shamans in China and over much of Asia. As early as 2400 bce, Indus Valley seals depict tiger-women and women dancing with tigers. In the early Shang dynasty, Yü bronzes of the early Shang dynasty show a tigress clasping children in her paws—possibly a clan ancestress, or a shamanic initiator—and tigers flank the head of a child being born on a colossal fangding. The taotie sign represents a tiger on innumerable Shang and Zhou offering vessels—and on masks. [On the taotie as tiger, Rawson, 244]

Mathieu Remi observes of the tigress form of Xi Wangmu, “There are good reasons for thinking that here we have a description of a shaman in trance.” He points to Chinese scholars who compare her staff to the staff of sorcerers. [Remi, 100, 481] Cahill draws the same conclusion, calling attention to modern parallels: “The stool, headdress, and staff—still part of the shaman’s paraphernalia in Taiwan today—reflect her shamanistic side.” [Cahill, 19]

Chapter 16 of the Shan Hai Jing returns to Xi Wangmu in the western wilderness. It describes “the mountain of Wangmu” in the country of the Wo people, who eat phoenix eggs. Whoever drinks the sweet dew of this place will be able to attain every desire. On the great mountain Kunlun is a spirit with a human face and a tiger’s body and tail. (Both are white, the color of the West and the goddess.) Finally, Xiwangmu is again described with tiger teeth and tail, with new details: she “lives in a cave,” on a mountain that “contains a thousand things.” [Remi, 575-78]

The Daren fu of Sima Xiangru concurs that Xi Wangmu lives in a grotto. In his account, the white-haired goddess is served by a three-footed crow and is unimaginably long-lived. [Remi, 481-2, 588] The ancient Huainan Zi contains the first written reference to Xi Wangmu granting the elixir of immortality. She bestows it on the Archer Yi, but his wife Chang E takes it and floats up to the moon where she becomes a toad (and the moon goddess). [Lullo, 270, 285] Xi Wangmu also grants longevity in the Songs of Chu. Seekers ask her for the divine nectar, or drink it, in many artistic depictions.

Kunlun

The marvellous Kunlun mountain lies somewhere far in the west, beyond the desert of Flowing Sands. It was often said to be in the Tian Shan ("heaven mountain") range of central Asia, and the source of the Yellow River. But Kunlun is a mysterious place outside of time, without pain or death, where all pleasures and arts flourished: joyous music, dancing, poetry, and divine feasts.[Cahill, 19-20, 77]Kunlun means “high and precarious,” according to the Shizhou Ji, because “its base is narrow and its top wide.” [Despeux / Kohn, 28] It is also called the Highgate or Triple Mountain. The Shan Hai Jing names it Jade Mountain, after a primary symbol of yin essence. In the Zhuang Zi, Xi Wangmu sits atop Shao Guang, which represents the western skies. Elsewhere she sits on Tortoise Mountain, the support of the world pillar, or on Dragon Mountain. In the Tang period, people said that the goddess lived on Hua, the western marchmount of the west in Shaanxi, where an ancient shrine of hers stood. [Cahill, 76, 14-20, 60]

The sacred mountain is inhabited by fantastic beings and shamanistic emissaries. Among them are the three-footed crow, the nine-tailed fox, a dancing frog, and the moon-hare who pounds magical elixirs in a mortar. There are phoenixes and chimeric chi-lin, jade maidens and azure lads, and spirits riding on white stags. A third century scroll describes Xi Wangmu herself as kin to magical animals in her western wilderness: “With tigers and leopards I form a pride; Together with crows and magpies I share the same dwelling place.” [Cahill, 51-3]

Medieval poets and artists show the goddess riding on a phoenix or crane, or on a five colored dragon. Many sources mention three azure birds who bring berries and other foods to Xi Wangmu in her mountain pavilion, or fly before her as she descends to give audience to mortals. The poet Li Bo referred to the three wild blue birds who circle around Jade Mountain as “the essence-guarding birds.” They fulfil the will of the goddess. Several poets described these birds as “wheeling and soaring.” [Cahill, 99; 92; 51-3; 159]

The Jade Maidens (Yü Nü) are companions of the goddess on Kunlun. They are dancers and musicians who play

chimes, flutes, mouth organ, and jade sounding stones. In medieval murals at Yongle temple, they bear magical ling zhi fungi on platters. In the “Jade Girls’ Song,” poet Wei Ying-wu describes their flight: “Flocks of transcendents wing up to the divine Mother.” [Cahill, 99-100]

Jade Maidens appear as long-sleeved dancers in the shamanic Songs of Chu and some Han poems. The Shuo wen jie zi defines them as “invocators [zhu] …women who can perform services to the shapeless and make the spirits come down by dancing.” [Rawson, 427] Centuries later, a Qing dynasty painting shows a woman dancing before Xi Wang Mu and her court, moving vigorously and whirling her long sleeves. [Schipper, 2000: 36] Chinese art is full of these ecstatic dancing women.

Tang poets describe Xi Wangmu herself performing such dances in her rainbow dress and feathered robe with its winged sleeves. In The Declarations of the Realized Ones she dances while singing about the Great Wellspring; the Lady of the Three Primordials replies in kind. [Cahill, 165-6, 187]

The Jade Maidens act as messengers of the goddess and teachers of Taoist mystics. They impart mystic revelations and present divine foods to those blessed to attend the banquet of the goddess. But the Book of the Yellow Court warns spiritual seekers against “the temptation to make love to the Jade Maidens of Hidden Time.” [Schipper 1993:144]

Sometimes Yü Nü appears as a single divinity, in connection with other goddesses. In Chinese Buddhism, she is the dragon king’s daughter, and presented to the bodhisattva Guan Yin. Or she is born from an appeal to Tian Hou (“Empress of Heaven”), a title posthumously bestowed on the coastal saint Ma Zi (who was syncretized with the goddess of the East). [Stevens, 167]

The immortals journey to Kunlun to be with Xi Wangmu. The character for immortal (xian) reads as “mountain person,” and alternately as “dancing person.” [Schipper: 2000:36] The goddess lives in a “stone apartment” within her sacred mountain grotto—from which spring the underground “grotto heavens” of medieval Taoism. It is the paradise of the dead; a tomb inscription near Chongqing calls it a “stone chamber which prolongs life.” [Wu, 83]

Xi Wang Mu is an eternal being who guides vast cosmic cycles. In her mysterious realm, the passage of time is imperceptible: “A thousand years are just a small crack, like a cricket’s chirp.” A visitor turns his head for a second, and eons have passed. When king Mu returns from his visit to her paradise, the coats of his horses turn white. [Cahill, 47; 84; 114-15; 129] The goddess of the West confers elixirs of immortality, even as she receives the dead and presides over their realm.

Mirrors and Tombs

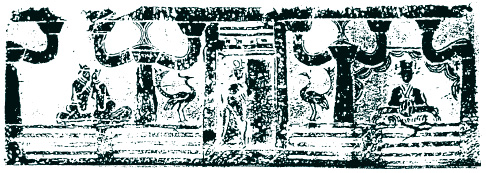

Ancient art is rich in iconography of the goddess: bronzes, murals, painted lacquers, clay tiles, and stone reliefs. Much of this art is from funerary contexts, befitting the signification of the West. The goddess sits with hands tucked into voluminous sleeves, on a throne perched above an irregular stone pillar or a multi-tiered mountain. An ancient lacquer bowl from a tomb at Lelang depicts her thus, wearing a leopard hat and sitting on a leopard mat, with a jade maiden beside her and a canopy above. [Liu, 40] Sometimes she is enthroned in pavilions or halls.

The goddess seated in pillared hall: sarcophagus from SichuanIn an important find near Tengzhou, Shandong, an incised stone depicts Xi Wangmu with a leopard’s body, tail, claws, teeth, and whiskers—and a woman’s face, wearing the sheng headdress. Votaries make offerings to her on both sides. The inscription salutes Tian Wangmu: Queen Mother of the Fields. [Lullo, 271] This alternate title reflects her control of the harvests, a tradition attested elsewhere. [Cahill, 13]

At Suide in Shaanxi, a sheng-crowned Xi Wangmu receives leafy fronds from human and owl-headed votaries, while hares joyously pound exilir in a mortar (below). The magical fox, hare, frog, crow, and humans attend her in a tomb tile at Xinfan, Sichuan. The tomb art of this province shows the goddess of transcendence seated in majesty on a dragon and tiger throne. [Liu, 40-3] This magical pair goes back to the Banpo neolithic, circa 5000 BCE, where they flank a burial at Xishuipo, Henan. [Rawson, 244] Tiger and dragon represented yin and yang before the familiar Tai Ji symbol came into use during the middle ages.

Tomb relief from Suide, ShaanxiThe Western Grandmother presides at the summit of the intricate bronze “divine trees” that are unique to Sichuan.

Their stylized tiers of branches represent the multiple shamanic planes of the world mountain. The ceramic bases for the trees also show people ascending Kunlun with its caverns. [Wu, 81-91] “Universal mountain” censers (boshanlu) also depict the sacred peak with swirling clouds, magical animals and immortals. [Little, 148]

Xi Wangmu often appears on circular bronze mirrors whose backs are filled with concentric panels swirling with cloud patterns and thunder signs. She is flanked by the tiger and dragon, or the elixir-preparing rabbit, or sits opposite the Eastern King Sire, amidst mountains, meanders, “magic squares and compass rings inscribed with the signs of time.” [Schipper 1993: 172] Some mirrors are divided into three planes, with a looped motif at the base symbolizing the world tree. At the top a pillar rests on a tortoise—a motif recalling the mythical Tortoise Mountain of Xi Wangmu. [Wu, 87]

Han dynasty people placed bronze mirrors in burials as blessings for the dead and the living, inscribed with requests for longevity, prosperity, progeny, protection, and immortality. Taoists also used these mystic mirrors in ritual and meditation and transmissions of potency. One mirror depicting Xi Wangmu bears a poem on the transcendents:

When thirsty, they drink from the jade spring; when hungry, they eat jujubes. They go back and forth to the divine mountains, collecting mushrooms and grasses. Their longevity is superior to that of metal or stone. The Queen Mother of the West. [Cahill, 28-9]The Goddess in popular movements

The Han Shu and other ancient histories indicate that the common people saw Xi Wangmu as a savior, protector, and healer in a time of severe drought and political disorder. A popular movement devoted to the goddess arose and spread rapidly. It reached its height in 3 BCE, as described as the Monograph on Strange Phenomena: “It happened that people were disturbed and running around, passing a stalk of grain or flax from one to another, and calling it ‘the tally for transmitting the edict.’” [Lulo, 278]The common people marched westward through various provinces, toward the Han capital. Many were barefoot and wild-haired (like their untamed goddess). People shouted and drummed and carried torches to the rooftops. Some crossed barrier gates and climbed over city walls by night, others rode swift carriages in relays “to pass on the message.” They gathered in village lanes and fields to make offerings. “They sang and danced in worship of the Queen Mother of the West.” [Lullo, 278-9]

People passed around written talismans believed to protect from disease and death. Some played games of chance associated with the immortals. [Cahill, 21-3] There were torches, drums, shouting. Farming and normal routines broke down. This goddess movement alarmed the gentry, and the Confucian historian presented it in a negative light. He warned the danger of rising yin: females and the peasantry stepping outside their place. The people were moving west—opposite the direction of the great rivers—“which is like revolting against the court.” The writer tried to stir alarm with a story about a girl carrying a bow who entered the capital and walked through the inner palaces. Then he drew a connection between white-haired Xi Wangmu and the dowager queen Fu who controlled the court, accusing these old females of “weak reason.” His entire account aimed to overthrow the faction in power at court. [Lullo, 279-80]

Change was in the air. Around the same time, the Taiping Jing (Scripture of Great Peace) described “a world where all would be equal.” As Kristofer Schipper observes, “a similar hope drove the masses in search of the great mother goddess.” [Schipper: 2000, 40] Their movement was put down within the year, but the dynasty fell soon afterward.

Yet veneration of the goddess crossed class lines, reaching to the most elite levels of society, as it had since Shang times. Imperial authorities of the later Han dynasty set up altars to the goddess. But courtly ceremonies differed from rural festivals, and religious interpretations were contested. Unfortunately, the Hanshu is the only written account of folk religion, from a hostile Confucian perspective. [Cahill, 24; Lullo, 277-81] The literati did not value peasant religion, so it was not recorded: “what is certain is that the religion of the common people, with its worship of holy mountains and streams, as well as the great female deities, was systematically left out.” [Schipper: 2000, 34]

Patriarchal revisions

From the Han dynasty forward, the image of Xi Wangmu underwent marked changes. [Lullo, 259] Courtly writers tried to tame and civilize the shamanic goddess. Her wild hair and tiger features receded, and were replaced by a lady in aristocratic robes, jeweled headdresses, and courtly ways. Her mythology also shifted as new Taoist schools arose. She remains the main goddess in the oldest Taoist encyclopedia (Wu Shang Bi Yao). But some authors begin to subordinate her to great men: the goddess offers “tribute” to emperor Yu, or attends the court of Lao Zi. [Cahill, 34, 45, 121-2] They displace her with new Celestial Kings, Imperial Lords, and heavenly bureaucracies—but never entirely.In the later Han period, the spirit-trees of Sichuan show Xi Wangmu at the crest, with Buddha meditating under her, in a still-Taoist context. [Little, 154-5; Wu, 89] By the Six Dynasties, several paintings in the Dun Huang caves show the goddess flying through the heavens to worship the Buddha. [Cahill, 42] (In time, Taoism and Buddhism found an equilibrium in China, and mixed so that borders between the two eroded.) But cultural shifts never succeeded in subjugating the goddess.

She held her ground in the Tang dynasty, when Shang Qing Taoism became the official religion. She was considered its highest deity, and royals built private shrines to her. Her sheng headdress disappears, and is replaced by a nine-star crown. Poets named her the “Divine Mother,” others affectionately called her Amah, “Nanny.” But some literati demote the goddess to human status, making her fall in love with mortals, mooning over them and despairing at their absence. In a late 8th century poem she becomes “uncertain and hesitant” as she visits the emperor Han Wudi. [Cahill, 82-3; 58-69; 159]

Others portrayed her as young and seductive. [Lullo, 276] Worse, a few misogynists disparaged the goddess. The fourth century Yü Fang Bi Jue complained about her husbandless state and invented sexual slurs. It claimed that she achieved longevity by sexually vampirizing innumerable men and even preying upon boys to build up her yin essence. But the vigor of folk tradition overcame such revisionist slurs—with an important exception.

The ancient, shamanic shapeshifter side of Xi Wangmu, and her crone aspect, were pushed aside. Chinese folklore is full of tiger-women: Old Granny Autumn Tiger, Old Tiger Auntie (or Mother), Autumn Barbarian Auntie. They retain shamanic attributes, but in modern accounts they are demonized (and slain) as devouring witches. Two vulnerable groups, old women and indigenous people, become targets. [ter Harrm, 55-76] Yet the association of Tiger and Autumn and Granny goes back to ancient attributes of Xi Wangmu that are originally divine.

In another shift, the Han elite invented a husband for the Western Queen Mother: the Eastern King Sire (Dong Wang Gong). As Susan Lullo observes, there is “no evidence in Han literature that the King Father ever existed in myth.” (There was a god of Tai Shan, the sacred mountain of the East, but he never seems to be coupled with Xi Wangmu.) The new husband was added to the eastern wall of tombs, opposite the Western Mother, for “pictorial balance”—but also to domesticate the unpartnered goddess. [Lullo, 273-4, 261]

The attempt to marry the goddess did not find favor in popular tradition. Two thousand years later after the Shang inscription to the Eastern and Western Mothers, folk religion continued to pair Xi Wangmu with a goddess of the East. Often it was Ma Gu or Ma Zi, goddess of the Eastern Sea, whose paradise island of Penglai was equivalent to Kunlun. Ma Zi is another eternal being who oversees vast cycles of time, as the Eastern Sea gives way to mulberry fields, and then back to ocean again. Some sources say that Xi Wangmu traveled to this blessed Eastern Isle. [Cahill, 118; 62; 77] These goddesses also share a title; like Wangmu, the name Ma Zi means “maternal ancestor, grandmother.” [Schipper, 166; Stevens, 137]Another Eastern partner of the goddess was Bixia Yüanjün, Sovereign of the Dawn Clouds. She was the daughter of the god of Mt. Tai, and her sanctuary stood on its summit. Bixia Yuanjün oversaw birth as her counterpart Xi Wangmu governed death and immortality. [Little, 278] A major shrine to Xi Wangmu stood along the path up this mountain. [Stevens, 53] The great poet Li Bo referred to “the Queen Mother’s Turquoise Pond” from which pilgrims drank while ascending Mount Tai. Stone inscriptions describe a rite of “tossing the dragons and tallies” in which monks threw bronze dragons and prayers for the emperor’s longevity into the waters of the goddess. [Cahill, 1-2, 59]

Taoist mysticism

From very ancient times the Grandmother of the West was associated with the tiger, the element metal, autumn, and the color white. These associations were part of the Chinese Concordance, which assigned to each direction (including the center) an animal, element, organ, emotion, color, sound, and season. Also known as Five Element or Five Phases, this concordance is the basis of Chinese medicine, astrology, and geomancy (feng shui).

Xi Wangmu is called Jin Mu Yüan Jün: Metal Mother, Primordial Ruler. [Cahill, 68] She is the great female principle, Tai Yin, which is also the name of the Lung meridian in Chinese medicine. It is linked to autumn, death, and grief. The goddess governs the realm of the dead, but is simultaneously the font of vital energy and bliss. A mural at Yongle Temple in Shanxi shows her with a halo, crowned with a phoenix and the Kun trigram that announces her as the Great Yin. Opposite her is a painting of the Empress of Earth. [Little, 276; 281]

The Book of the Center says that Xi Wangmu is present in the right eye. “Her family name is Great Yin, her personal name, Jade Maiden of Obscure Brilliance.” [Schipper, 1993: 105] The Shang Jing Lao Ze Zhong Jing accords on these points and instructs adepts how to manifest celestial beings within their bodies. It names her “So-of-itself,” “Ruling Thought,” and “Mysterious Radiance.” [Cahill, 35]

In Taoist mysticism the human body is the microcosm that reflects the terrestrial and celestial macrocosm, and these themes are interwoven in traditions about the goddess. Kunlun is present in the body as an inverted mountain in the lower abdomen, at the center of the Ocean of Energies (Qi Hai). The navel is the hollow summit of the mountain, through which the depths of that ocean can be reached. This is the Cinnabar Field (lower Dan Tian), the “root of the human being.” [Schipper 1993: 106-7]

On the celestial level, the goddess also manifests her power through the Dipper Stars, a major focus of Taoist mysticism. [Schipper, 70. He notes that Ma Zi was also seen “as an emanation of one of the stars in the Big Dipper.” (43)] A Shang Qing text dating around 500 says that Xi Wangmu governs the nine-layered Kunlun and the Northern Dipper. The Shih Zhou Zhi also connects Kunlun mountain “where Xi Wang Mu reigns” to a double star in the Big Dipper, known as the Dark Mechanism. The Dipper’s handle, called the Jade Crossbar of the Five Constants, “governs the internal structure of the nine heavens and regulates yin and yang.” [Cahill, 35-8]

Taoist texts repeatedly associate Xi Wangmu with nine planes, a nine-leveled mountain, pillar, or jade palace. She is worshipped with nine-fold lamps. She governs the Nine Numina—which are the original ultimate powers in Shang Qing parlance. The goddess herself is called Nine Radiance, and Queen Mother of the Nine Heavens. [Cahill, 68-9, 126]

Around the year 500, Tao Hung Jing systematized Taoist deities into two separate hierarchies, male and female, with Xi Wangmu ranked as the highest goddess. He gave her a lasting title: The Ninefold Numinous Grand and Realized Primal Ruler of the Purple Tenuity from the White Jade Tortoise Terrace. Other sources, such as the poet Du Fu, describe her as descending to the human realm enveloped in purple vapors. [Cahill, 33; 24; 168]

Teacher of Sages

Taoists recognized the ancient great goddess as a divine teacher and initiator of mystic seekers, and in many cases as the ultimate origin of their teachings and practices. She governs the Taoist arts of self-transformation known as internal alchemy, including meditation, breath and movement practices, medicines and elixirs. Books say that the legendary shamanic emperors Shun and Yü studied with Xi Wangmu. They also credit her as the source of wisdom that the Yellow Emperor learned from the female transcendents Xüan Nü and Su Nü. Over time the goddess comes to be portrayed as a master of Taoist scriptures, with a library of the greatest books on Kunlun. [Cahill, 14-15; 44; 34]Legend said that the Zhou dynasty king Mu (circa 1000 bce) travelled to Kunlun in search of the Western Mother. Many ancient sources elaborated on their meeting beside the Turquoise Pond. The emperor Han Wudi was granted a similar audience in 110 BCE. The Monograph on Broad Phenomena says that the goddess sent a white deer to inform him of her advent, and he prepared a curtained shrine for her. She arrived on the festival of Double Sevens, riding on a chariot of purple clouds. She sat facing east, clothed in seven layers of blue clouds. Three big blue birds and other magical servitors set up the ninefold tenuity lamp. The goddess gave five peaches to the emperor. He wanted to save the seeds for planting, but she laughed and said that they would not bear fruit for 3000 years. [Cahill, 48-55]

In a later account, the cloud carriage of the goddess is drawn by nine-colored chimeric chilin. She wears a sword, a cord of knotted flying clouds, and “the crown of the Grand Realized Ones with hanging beaded strings of daybreak.” She granted the emperor a long instruction on how to attain the Tao—which he failed to follow. Instead of nourishing essence, preserving breath, and keeping the body whole, he lost himself in carousing and indulgences. [Cahill, 81, 149-153]

Literature focuses on her meetings with emperors, but a deep and broad tradition casts Xi Wangmu as the guardian of women and girls. They worshipped her at the birth of daughters, and she protected brides. [Stevens, 53] Celebrations of women’s fiftieth birthday also honored the goddess. Women who stood outside the patriarchal family system were regarded as her special protegees, whether they earned their own way as singers, dancers, prostitutes, or became nuns, hermits, or sages who attained the Tao. [Cahill, 70]

Though men greatly outnumber women as named and remembered Taoist masters, in practice women acted as teachers and libationers. Female instruction was built in to a greater degree than any “major” religion; tradition demanded that initiation be done by a person of the opposite sex, and the highest degree of initiation “could only be obtained by a man and a woman together.” [Schipper 1993: 58, 128-9]

Many accounts show Xi Wangmu as the ultimate source of teachings transmitted by female sages and transcendents to mortal men. The Zhen Gao scroll lays out a complete spiritual matrilineage that begins with Xi Wangmu and enumerates clans and religious communities in the female line. [Cahill, 34] The female immortal Wei hua-cun was said to have transmitted teachings to the shaman Yang Xi. Shang Qing Taoism arose from her revelations, but it was understood that they were inspired by the Spirit Mother of the West. [Schipper 2000: 44; Cahill, 155] Shang Qing tradition also holds that the female transcendents Xuan Nü (the Dark Woman) and Su Nü (Natural Woman) had taught the Yellow Emperor.

Qi Xi, or the Night of Sevens

Over the centuries the Double Sevens festival drifted away from Xi Wang Mu, and toward the Weaver Girl. This night was the one time in the year that she was allowed to meet Cowherd Boy. An ancient legend says that the god of heaven separated the lovers, or in some versions, Xi Wangmu herself. Angered that the girl was neglecting her loom, she made her return to the heavens. When Cowherd followed, the goddess drew her hairpin across the sky, creating the celestial river of the Milky Way to separate the lovers. (They were the stars Vega and Aquila.) Later, she helped them to reunite by sending ten thousand magpies to create a bridge. So the holiday is sometimes called the Magpie festival.

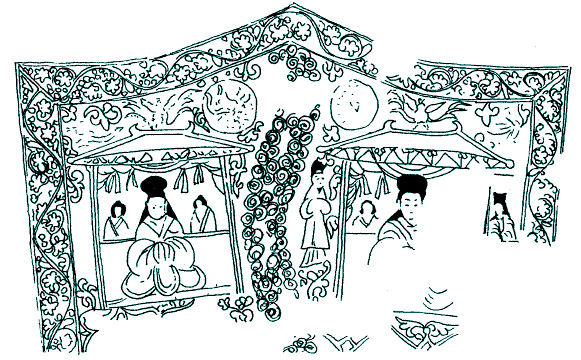

In this tomb art from Guyuan in Ningxia, it is Xi Wangmu and Dong Wanggong who are separated by the Milky Way, not the Weaver Girl and Cowherd, showing that there were a range of stories around these themes.In other versions, Weaver Girl is a fairy whose work is to weave colorful clouds in the sky. The cowherd surprises her and her six fairy sisters swimming in a lake. He steals Weaver Girl’s clothes (or all of them) and she is forced to marry him. This angers the goddess of heaven, who commands her to return to heaven.

Xi Wangmu’s connection to weaving has faded, just as her sheng headdress was dropped from Taoist iconography. Now it is Weaving Maid who oversees women’s fabric arts, silk cultivation, and needlework. She rules “the fecund female world of seedy melons and fruits” and “the gathering and storing of precious things.” Yet this too connects her with ancient goddess, whose “numinous melon produces abundantly” every four eons. [Cahill, 77]

The drift of mythic themes pops up in various places. The magpies who form the reunion bridge are sacred to Xi Wangmu. The Milky Way separates not the ill-starred lovers, but the Western Mother and the Eastern King, on a painted coffin in Ningxia. [Liu, fig. 43] Xi Wangmu was traditionally the controller of the North Dipper, but in the famous mystic diagram from Baiyuan Guan, Cowherd is holding the constellation. A Double Sevens song in the Yangzi region invokes the Eastern goddess for transcendent powers: “On this night we should beg for the techniques of immortality, clawing away some of Ma Gu’s medicine to cure the Lady in the Moon.” [Mann, 173

As before, the festival “marked the beginning of autumn,” when ghosts are propitiated and women begin to sew winter clothes. On this day they wash their hair with herbal infusions, spread out offerings of melon and fruit seeds, and atttempt to thread needles by moonlight: the “test for skill.” [Mann, 170, 173] From this custom the festival came to be called the Night of Skills, or Pleading for Skills.

The holiday was “extremely popular among unmarried girls” in the Canton Delta, the year’s best festival. In this region of delayed marriage and sworn spinsters, it is called the Festival of Seven Sisters. Its story does not focus on the lovers, but on the Weaving Maid and her sisters. (Here it is the sisters who became furious at the Weaver Girl’s marriage, and who only permitted her to cross over to her husband once a year.) Women propitiate the Seven Sisters “with elaborate displays of their needle and handicraft skills.” They create altars with candles, incense, flowers, fruits, and finely decorated miniature clothing, shoes, and furniture, all in sevens. The celebration culminates with a “wish-fulfilment banquet.” [Stockard, 42-4]

By the late Ming period, the mixture of Buddhism and Taoism gave rise to a new goddess with attributes of Xi Wangmu and Guanyin: Wusheng Laomu. This Venerable Eternal Mother “created the world in the beginning of time.” She helps and teaches her children—who go to her western paradise at death. [Despeux, 42]

The visionary Tanyangzi was from childhood devoted to Guanyin and Amitabha. Born in 1558 as Wang Taozhen, she meditated and was reluctant to marry. Her parents betrothed her but the fiance died soon after, and the maiden embraced the status of widow, making it possible to remain unwed. She had visions of an unimaginably beautiful “Supreme Perfected.” From this “great goddess,” Tanyangzi received a transmission of a smoky mystic character which she breathed in and absorbed into her body. This initiation enabled her to go without eating and resist sexuality and physicality. At the age of nineteen, Tanyangzi was said to have ascended to Kunlun, where she met Xi Wangmu and received immortality. Yet she died a few months later. [Despeux, 45] Here the Taoist and Buddhist themes are mixed in somewhat contradictory ways! Taoists did not reject sexuality, and their intepretation of immortality did not imply leaving the body behind

Women’s embroidery kept the Western Spirit Mother alive. Their favorite scene seems to have been the goddess flying on a phoenix toward her mountaintop garden, with the Jade Maidens assembled to welcome her return and the peaches of immortality ripening beside the Turquoise Pond.

Left: modern statue of Xi Wang Mu holding a peach of immortality

Notes

Cahill, Suzanne E. Transcendence and Divine Passion: the Queen Mother of the West in Medieval China. Stanford CA: Stanford University Press, 1993

Schipper, Kristofer, The Taoist Body, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993

Little, Stephen, and Shawn Eichman, Taoism and the Arts of China, ed. Stephen Little, Chicago: Art Institute, 2000

Wu Hung, “Mapping Early Taoist Art” in Little, 2000

Schipper, Kristofer, “Taoism: the Story of the Way” in Little, 2000

Goldin, Paul R. “On the Meaning of the Name Xi Wangmu, Spirit-Mother of the West,” in Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 122, No. 1, Jan.-Mar. 2002

Liu, Yang, “Origins of Daoist Iconography,” in Ars Orientalis, Vol 31. Smithsonian and University of Michigan, 2001

Remi Mathieu, Etude sur la mythologies et l’ethnologie de la Chine ancienne: Traduction annotée du Shanhai Jing, Vol. I, Paris: Institut des hautes etudes chinoises, 1983

Strassberg, Richard, A Chinese Bestiary: Strange Creatures from the Guideways Through Mountains and Seas. ••••

Birrell, Anne, The Classic of Mountains and Seas, ••••

Feng, Gia-fu and Jane English, Chuang Tsu: Inner Chapters, New York: Knopf, 1974

Sun Ji, “Wei-Jin shidai de ‘xiao’,” in Yang Hong and Sun Ji, Xunchang de jingzhi-Wenwu yu gudai shenghuo. Liaoning: Jiaoyu Chubanshe, 1996 [Thanks to Yun of the China History Forum for translating key passages.]

Despeux, Catherine, and Kohn, Livia, Women in Daoism. Cambridge MA: Three Pines Press, 2003

Rawson, Jessica, “Tomb of the king of Nanyue,” in The Golden Age of Chinese Archaeology, ed. Xiaoneng Yang, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999

Stevens, Keith, Chinese Gods, London: Collins & Brown, 1997

ter Haarm, B. J. Witchcraft and Scapegoating in Chinese History. Leiden: Brill, 2006

Mann, Susan. Precious Records: Women in China’s Long Eighteenth Century. Stanford University Press, 1997

Stockard, Janice. Daughters of the Canton Delta: Marriage Patterns and Economic Strategies in South China, Stanford University Press, 1992

Copyleft by Max Dashu. May be reproduced with attribution, if excerpts are not changed.