The Midsummer Dancers

by Max Dashú

How people dealt with distress in a time of extremity by reviving the old pagan dances.

Midsummers Day was holy all over Europe. Irish and Scots, Swiss and French, Germans, Lithuanians, Italians, Russians, and Swedes celebrated the climax of the light with celebratory rituals. At midnight on the holyday's eve, said Spanish tradition, the waters are blessed with special power. Maidens rushed to be the first to reach the springs. The first to drink the water received its "flower," and left a green sprig to show others that it had been collected. People brought this water home as medicine. They took off clothing and shoes to bathe in the Midsummer's eve dew, which had blessing and curative powers.

Everything was possible on this night of mysterious power. The dark sky was alight with bonfires, and people dancing around them, singing "Long live the dance and those who are in it/Señor San Juan! / Even the stars will join in/ Viva la danza y los que en ella están!" Long live the dance and those who are in it!” The Church had succeeded in renaming Midsummer’s Day after one of its saints, but not in eliminating the ancient customs.

At sunrise the sun dances with joy, and the entire world is washed clean, full of grace. The xanas emerge from their wells and caves, combing their long hair, and people sought gifts of abundance from them. (Xanas are faeries whose name is derived from the Roman dianae, or dianas.) At Salas tradition prescribed going to the xana's fountain on St John's morn to say, "Xana, take my poverty / Give me your wealth." [Canellada, 249, 262]

In the Harz mountains Germans kept up a custom of dancing around a tree of life on the summer solstice. They cut a tall fir, shaved off the lower bark leaving its top green, decked it with flowers and eggs. They put this sanctified tree in the center of their midsummer ritual, and came dressed in their festival best to play music, sing, and dance rounds.

In Sweden, dancers coursed around a tall, straight pine that they had ritually set up and decorated. [Frazer, 141] Midsummer poles were raised in many parts of Ireland, dressed with flowers and ribbons and cloths, and crowned with ginger-cakes. Musicians played beneath the pole as dancers competed in hopes of winning the cakes. [Wood-Martin, 264] All over Europe, people danced with wreaths on their heads, hopping and leaping to the music of bagpipes and handclapping. [Backman, 270-76]

Midsummers became the focus for a revival of pagan culture in the mid-to-late 1300s. Trance dancing spread through southern Italy and the Rhineland. Large groups of people danced the round with deep emotion, for days at a time. These gatherings were large enough to attract the notice of chroniclers. The dancers appear in Erfurt, Germany, in annals of the year 1237, and again in 1278 in Utrecht, Holland. The earliest records of ecstatic dancers call them St. John's Dance, after the saint assigned to Midsummer Day. (The later name of St Vitus' Dance points to the same time frame; that saints' festival fell on June 15th.) The dances took place on and around the summer solstice. [Backman; McCollogh]

In 1373 and 1374 a mass celebration of dancers spread over Flanders and western Germany. At Aachen people danced through the streets in circles, leaping and singing with religious intensity. The dancers entered trances, sinking to the ground unconscious, and later sat up and recounted their visions. Some prostrated themselves before images of the Virgin in churches. Most of the dancers were poor folk, with a large proportion of women. [Lea, Inq, 393-4; McColloch, 246-7]

Basque woman musician

Peasants dancing with festival wreaths

This popular upwelling alarmed officials of church and state, who saw it as uncontrollable, with people traveling from place to place, and probably demonic. In the 1380s the monk Petrus de Herenthal quoted a chronicler who wrote:

A certain new sect arose at this time. With manners and looks ne'er seen before. The people danced and leaped violently. One lightly touched another's hand, then shrieked. "Frisch, Friskes,” women and men cried it with joy. Each one had a towel tied on, and a stave. A wreath was set on every head. [Backman]

Petrus de Herenthal wrote that the dancing had started with people coming from different parts of Germany, some of whom made it as far as France. Like other priestly interpreters of the phenomenon, he described the entranced dancers as tormented by the devil.

... in markets and churches, as well as in their own homes, they danced, held each others' hands and leaped high into the air. While they danced their minds were no longer clear, and they paid no heed to modesty though bystanders looked on. While they danced they called out names of demons, such as Friskes and others... [Backmann, p 191]

But Frisch or Friskes was not the name of any devil. The medieval German word frisch or vrische, and related terms in Flemish, Dutch and French, had to do with healing and lifeforce. As E. L. Bachman pointed out, “Vrische is also a verb with the meaning, 'make whole'... East Frisian has frisk, which means 'healthy, young, unspoiled, lively' and frisken, meaning 'to make healthy...” Its English relative is frisky, “lively, frolicking", and the Scandanavian versions mean “fresh." [Backmann, 226-7] The dancers were singing the praises of wholeness, vitality, and health, not “devils never before heard of,” as the historian Radulphus de Rivo wrote. In Holland the dancers themselves were called Friskers. [Schaff, c 502]

Priestly accounts accuse the entranced dancers of being possessed and questioned whether they were christians. An old Belgian chronicle described them with the verse Gens impacata cadit / Dudum cruciata salvat: "people restively fall, doubting the cross saves." [Bachmann, 201] "A contemporary poem speaks of their being opposed to the faith, haters of the clergy, and indifferent to [its] sacraments." [McColloch, 256-7]

The Liege Chronicle of 1402, also written by a monk, says that the dancers first came to Liege for the consecration of the Mary Church, where they leaped and danced before the altar: "On their heads they bore a sort of wreath, and as they leaped they cried 'Frilis'."[Bachman, 199] The wreaths, leaping dances and gathering at Marian shrines turn up in other descriptions of the wandering dancers. Johan of Leyden wrote that they wore wreaths on their heads and kept crying out, “Frijsch, Frijsch” as they danced. [Bachmann, 200]

A much later version in Koelhoff's Chronicle of 1499 has the dancers shouting as they leap, “Oh Lord St John/so, so/ Whole and happy, Lord St John!” [Bachmann, 203] The word Frisch is no longer being used, but its meaning is retained (and confirmed). Fragments of the old call survived in the Fulda region's midsummer bonfire cry: Haberje, haberju! fri fre frid! [Grimm, 618]

Across Europe it was customary to dance around Midsummer bonfires. The Swedes used nine kinds of wood in their blaze, and wove nine kinds of flowers into the dancers' garlands. In many places people gathered nine special herbs, usually including hypericum and mugwort. The Spanish gathered verbena at dawn and leaped over the fires (as the Catalans still do). The Letts sang and gathered hypericum and a plant called raggana kauli, "witch’s bones." People observing these old pagan customs were called "John's folk," after the saint whose day fell on the old pagan festival. [all Grimm, 1467]

Mugwort, Artemisia Vulgaris

Herbs in the Artemisia family are regarded as sacred in North America (desert sage, among others, has purifying powers), China (where it is used in moxibustion smudging by acupuncturists) and Europe, where it also was used as a smudge to remove negative influences and was said to protect those who wore it.One of the most common herbs gathered and worn at Midsummers was hypericum, whose popular name "St John's wort" comes directly from its connection with the folk festival. In France the “herbs of St Jean” included yarrow, vervain, armoise, glaieul, joubarbe, lierre terrestre, millepertuis, sureau, sauge and serpolet. [Benoit, 81] Some sources tell us the wreaths were made out of wormwood and hypericum, Both of these blessing herbs traditionally gathered at Midsummers and made into garlands to hang up in homes and barns, as protective talismans, and sometimes used to smudge in ceremonial blessings and healing rites. Last years' garlands were thrown into the bonfire.

When Petrarch visited Cologne on Midsummer Eve in the year 1330, he found the banks of the Rhine crowded with women adorned with chains of aromatic herbs. Just at sunset they dipped their arms and hands in the water and washed them to the accompaniment of certain words in order to wash away all manner of evil for a year to come. Frequently they also hung such wreaths and garlands of greenery and flowers over the streets of the towns in the Rhine province and in Flanders in order that the children might dance under them... [Backman, 274]

Several contemporary sources say that bands of celebrants came from upper Germany or Bohemia, leaving their homes and kin to travel about. De Rivo’s chronicle says that “there came a curious sect of people from the upper regions of Germany..." while Johannes de Beka wrote that the movement had its “in the kingdom of Bohemia.” [in Backman, 194; 198]Backman turned up an interesting precedent for the Dancers movement that took place on the borders of Bohemia in 1349, at the height of the plague. In Lusitze some women and girls began to “act crazily," dancing and shouting in front of an image of Mary. They said that she spoke to them, and took to the roads, travelling from Torgowe to Interbok, gathering a crowd of people as they went, until the duke of Saxony refused to allow them in his domains. [Bachman, 190, from the Magdeburg Schoppenchronik of 1360. Lea, II, 343, calls this “an outbreak of women from Hungary, which was summarily suppressed in Saxony.”]

It is quite possible that Europeans revived trance dancing as a way of confronting the plague. We have already seen how the dancers invoked healing power with their cries of "Friskes!" We know that in 1349 the people of Wertheim tried to ward off the plague by performing ringdances around a pine tree. [Backman, c 5] The church had always recognized and condemned the animist and pagan roots of these ecstatic ceremonies.

Now, at the end of the middle ages, churchly prohibitions against dancing reach their highest pitch. They single out for condemnation "the participation of women and... crude magical churchyard dances." [Backman, 331] Chroniclers made no secret of their contempt for the celebrants, especially “the women and young girls who shamelessly wandered about in remote places under the cover of night.” [Chronicler cited in Bachmann, 207] Well into early modern times, the writer Schlager was still commenting that "loose" common women danced at the Midsummer fire. [Grimm, 1467?]

A new wave of dancing started in 1381 near a chapel of St John by the river Gelbim. The ecstatic dance took place in a forest secluded from the view of would-be exorcists, who had begun to claim that the dancers were possessed by devils.

... in one lonely spot in the diocese of Trier, far from the abodes of men, near the ruins of a deserted old chapel, there gathered several thousand members of this company [societas] as if to fulfil a sacred vow. They and others who followed to see the show amounted to some five thousand persons. There they stayed, preparing for themselves a kind of encampment: they built huts with leaves and branches from the nearby forest, and food was brought from towns and villages as to a market. [Bachmann, 207; my italics]

The music and songs of these dancers are lost to us, but the deliberate and ceremonial nature of the dance-gathering is clear. Near the turn of the century Johannes de Beka wrote about another outbreak of entranced dancing in 1385:

In the same year there spread along the Rhine, beginning in the kingdom of Bohemia, a strange plague which reached as far as the district of Maastricht, whereby persons of both sexes, in great crowds, marched here and there bound around with cloths and towels and with wreaths on their heads. They danced and sang, both inside and outside the churches, till they were so weary that they fell to the ground. At last it was determined that they were possessed. The evil spirits were driven out.... [Backman, 198]

The lauding of successful priestly exorcisms does not mesh with the chronicles' assertion that the “choreomaniacs” kept on going from city to city. Rather than disappearing under dramatically successful ministrations, as the clergy claimed, the dancers passed through Flanders and Holland and then headed towards southern Germany.

In 1418 a crowd assembled to watch women dancing in the Water Church of Zurich. This chapel had been built over a spring reknowned as a source of healing and strength-giving waters for centuries. [Bachmann, 232] Other gathering points were places associated with rites of the summer solstice. At St John's Mount near Dudelingen, Midsummer was celebrated with dancing that culminated with people falling to the ground unconscious. This site continued to be a place of pilgrimage for centuries; in 1638 Bertelius wrote that “even today” large crowds came there in procession.

Trance dance remained common practice through the 1400s. The priesthood disparaged it but peasant festival celebrants kept it alive. Only in 1518 did it come to be known as St Vitus' Dance, after the patron saint of seizures, spasms and rabies, when priests performed exorcisms on dancers at the chapel of St Vitus in Strasbourg. Perhaps they had decided that the pagan associations of “St John's” festival had become problematic.

Contemporary chronicles tell us that this rather desperate outbreak of dancing took place in a year preceded by several years of ruined harvests and famine. Several chroniclers agree that a woman began dancing for days at a stretch, that 34 others soon were dancing, and within a month more than 400 had taken to dancing and hopping “in the public market, in alleys and streets, day and night...” [Chron. MS Argent, in Backman, 237] People fasted and danced continually “until they fell down unconscious.” [Strasbourg chronicle, in Backman, 238]

The authorities were at a loss about how to suppress this popular movement. They tried to keep the dancers indoors and to make the guilds responsible for taking their dancers to the shrine of some saint. None of this worked, so finally they outlawed the playing of music.

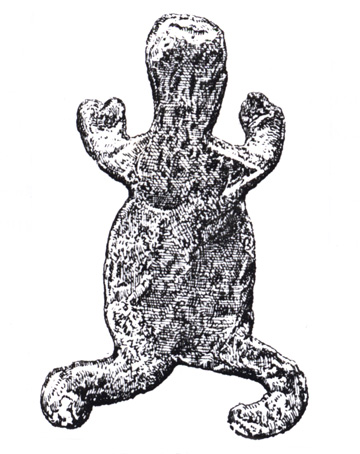

Votive frog

from the grotto of

HohlensteinE. L. Backman thinks that the dancers chose the mountain chapel of St Vitus because of its Hohlenstein grotto. The saint was associated with cures through blessed water at this pre-christian shrine. Women had a custom of offering iron toads at this grotto, which they continued to do into modern times. An 18th century cardinal felt called upon to forbid the placing of these and “other superstitious images," including human forms. [Backman, 238-43]

This pagan rite of the frog or toad evoked very old associations with witchcraft and prophecy. Germans called the toad hexe, Italians fata, Poles czarownica, Ukrainians bosorka, Serbs and Croats gatalinka, the Greeks mantis: all names meaning "witch" or "prophetess." [Gimbutas, Language of the Goddess, 256] But “toad” also had also become a pejorative name for women, as in the Bavarian epithet heppin, even though toads were also called muml, “auntie.” [Grimm, 1492] Basque folklore pictured witches as tending flocks of toads, and in witch trials women were accused of turning into toads, while other accusers claimed that toads feet were visible in the pupils of witches’ eyes.

Women offered toads fashioned in wax, wood, iron or silver to Mary at churches in Bavaria, Austria, Hungary, Moravia and the Balkans, as Marija Gimbutas described. "Some of these ex-votos have human heads, others bear the sign of a vulva on the underside, while many have a cross on the back." She noted that these frog offerings go back a very long time in the eastern Alps, dating to 1000 BCE at Maissau, lower Austria, while others are known from Greece (6th century BCE) and Etruria. Women used them to conceive children and to ensure safe births. [Marija Gimbutas, Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe, 177-8]

In Peter Breugel's "St Vitus" drawings, women are the central figures, flanked by pairs of men. His notes say the dancers had to pass over running water on a bridge, recalling animist belief in the curative powers of running waters as well as early medieval legends of pagan dancers on the bridge who were forced to keep dancing when cursed by a priest. Seventeenth century sources also name women as those seized with the dance-mania. They still flocked to curative chapels. If they danced and became entranced before St Vitus' day (June 15), it would "cure" them for the year. [Backman, 252-3] These developments are reminiscent of the tarantella, also a primarily female trance dance (“possession cult” in scholarly parlance).

The strategy of branding the dancers as out-of-control maniacs ultimately succeeded. Trance dancing came to be viewed with contempt in Western Civilization. The dancers are described, with the same contempt later directed at the vodunsis and santeros of Afro-Caribbean sacramental dance, as mad people held captives by superstition and delusion. Diabolism was projected on these groups, and many others, by a hostile priesthood who became the primary (and sometimes the only surviving) historical sources.

The medieval movement of ecstatic dancers arose at a harrowing time in European history. Mystic ecstasy was a medicine for desperation, a last public outpouring of shamanic culture in the midst of political upheaval and economic distress.

Bibliographic Notes

I rely heavily here on a little-known, important and erudite book by E. Louis Backman, Religious Dances in the Christian Church and in Popular Medicine, George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London, 1952

Schaff, David S. and Philip, History of the Christian Church, Scribner's Sons, NY 1910

Lea, Henry Charles, A History of the Inquisition of the Middle Ages, Harper and Bros, NY 1901

Canellada, Maria Josefa, Folklore de Asturias: Leyendas, cuentos y tradiciones, Ayalga Ediciones, Spain, 1983

Wood-Martin, W.G., Traces of the Elder Faiths of Ireland: A Handbook of Irish Pre-Christian Traditions, Vol II, London 1902

Grimm, Jacob, Teutonic Mythology, translated from 4th edition by James S. Stallybrass, George Bell & Sons, London, 1883

McCulloch, Canon, Medieval Faith and Fable, George Harrap & Co, London, 1932

The Suppressed Histories Archives