Female Divinity in South America

Max Dashú

First there was the sea. All was dark. There was no sun, no moon, nor people, animals or plants. Only the sea was everywhere. The sea was the Mother. She was water and water in every direction and she was river, pool, waterfall and sea and so she was everywhere. So, at the beginning, only the Mother was. She was named Gaulchováng.

So say the matrilineal Kogi people of the Santa Marta mountains in Colombia. Descendants of the glittering Tairona civilization, they base their entire cosmology on a primordial Mother Essence from whom everything originates, in the darkness. She is the unborn and eternal source. She is the Mother of Songs.

The Mother was not human, or nothing, or anything. She was aluna. She was the spirit of what was to come and she was thought and memory. So the Mother existed only in alúna, in the lowest world, in the ultimate depths, alone.

The Kogi say that this power of aluna exists in everything, and gives rise to all that exists. (Montoya Sanchez, 63) After unknown ages, the Mother began to bring the first world into being. Lands began to form above in the darkness, and in successive worlds, spirit people without bones, and later a Father Sai-Taná, and people with limbs and heads. In the fifth world, the Mother commanded that the ancestral beings speak. Their bodies continued to take on form, and their blood. In the ninth world the ancestral pair found a great tree and heaven above the waters, and built a great house there.

The Kogi (also known as Kágaba) say that their ceremonial “house of the sun” is like this first house, a circular building with a womblike opening to the heavens. Since the Spanish conquest, it is known as cansamaria (“house of Maria”), although the Kogi did not convert to Catholicism. Another account says that the Kogi “believe that the world was created by the great mother Gauteovan who created the sun from her own menstrual blood, and who is also the origin of everything else in the world…” She is the Mother of Songs. (Trimborn, 86-7)

Other Colombian peoples echo this cosmogony of the primordial Mother. On the Guajira peninsula, the matrilineal Wayúu say that Night was the great mother, and heaven’s Light, the great father. Each had twins: his were the sun and moon; hers were earth and sea. Sun fertilized Sea and her son Rain fertilized Earth, from which all the spirits, plants, animals and humans came forth. (Vizcaino,13) The Wayúu speak of her as “the great mother Mma, the earth.” (Vizcaino, 83) As Renilda Martinez told the International Earth Summit in Brazil in 1992: “Wayúu elders tell us that we are children of Juya (rain) and Mma (Earth) and that the trees, mountains and animals are our relatives. We conceive of the earth as a fountain of sustenance. She is the creator of life...” (Martinez, 9)

The goddess Dobeiba was the primary deity in the Isthmus region of Colombia. A river and the country Dabeiba were named after her. She was a storm goddess and culture-giver. The “house of Dobeiba” was a temple full of gold and precious stones, said to be guarded by a puma, and people made pilgrimages to it. (Montoya Sanchez, 102-3) While the early missionary Petrus Martyr emphasized tales of a masculine creator, he admitted, “They believe that Dabeiba, the divinity universally venerated in the country, is the mother of this creator,” and noted that he was much less worshipped than she was. (Alexander, 191)

Similar 16th century accounts say that the people of Antioquía venerated the goddess Dabeiba. More recent testimony from the Catío people describes Dabeiba as a beautiful woman of ancient times who taught the people agriculture, how to weave baskets, mats, and fire-fans, how to make pots and body-painting and to dye the teeth black. Then she ascended back to the sky. She brings storms and earthquakes. (Montoya Sanchez, 60-1)

Quimbaya breastplate of beaten gold, Colombia. See more:Another important Colombian goddess tradition comes from the Chibcha. They revered an ancestral mother known as Fura-Choguá, “good woman” or, more frequently, as Bachué, “big-breasted one.” Soon after light appeared and the world came into being, she emerged from a mountain lake, carrying a three-year-old child. Bachué made her home in Iguaque, where she raised this son. When he matured, she married him, bearing four to six children at each birth. Their descendants populated the earth. She taught her people wisdom, how to live, and many arts, including agriculture.

After a long time Bachué and her son-husband left Iguaque, calling the people to follow them to their lake in the mountains. There, friar Pedro Simon related, “she made a speech exhorting the people to live in peace and conservacion, to keep the laws and precepts she had given, which were not few, especially in the matter of the divine rites…” Then Bachué and her consort turned themselves into huge snakes and returned to the sacred lake. But people said that she appeared again in many places. All the Chibcha worshipped her, especially in agricultural ceremonies around food crops, and made images of her and her son. (Noticias Historiales by Fray Pedro Simón, Vol II, pp 228-9, in Montoya, 77) The only offering to Bachué was the burning of resinous incense at sacred springs. All snake divinities belonged to her veneration. (Trimborn, 92)

The Chibcha also revered the rainbow goddess Chuchabiba, who protected expectant mothers. The moon goddess Chía, whose temple in Cundinamarca was an important religious center. (Trimborn, 90) She was also known as Huitaca, who some see as a form of Bachué. She challenged the patriarchal prophet Bochica, who established institutions favoring men: “The goddess Huitaca appeared in this new situation that gave men more power, a beautiful woman of great resplendance who preached her rebellion against patriarchy and the necessity of a broad life, open, full of games, pleasure and drunkenness.” Bochica turned her into an owl, or alternatively, threw her into the sky where she became the moon. (Ocampo, 58)

Another Chibchan-speaking people, the Kuna of Panama, speak of Nana Dumat, the Great Mother, as the “Path on which we have come.” Her partner Baba helped her in the creation, and they form a unity. Nana Dumat gives birth to all life. The Nila, three beautiful women who descended from sky, were prophets who brought culture to the Kuna. (Olowaili, 2005)

In Ecuador, Cieza de Leon reported, the people of Manta venerated a goddess who lived in a huge emerald and healed diseases. Emeralds and other gifts were offered to her. The early Spanish writer Velasco said that she was called Umiña. (Estrada, 76ff) Garcilaso de la Vega wrote that this emerald was the size of an ostrich egg, and was displayed in the great festivals. People came from great distances to worship the goddess and make offerings, including emeralds which were regarded as her “daughters.” The Spanish looted the gems, but the Manteños had already hidden away the sacred one before they arrived. (Saville, 105)

During colonization, Catholic names were attached to indigenous goddesses. The most famous example in South America is the assimilation of Pachamama, the Quechua Earth Mother, to the Virgin Mary or her mother, Santa Ana. (See article XXX) A 1525 Spanish account refers to a goddess worshipped on Salango island off the coast of Ecuador. It says that her tent sanctuary was “draped with rich embroidered mantles, where they have an image of a woman with a child in her arms whom they call Maria Meseia: when someone has an affliction in some part (of the body), they make a copy of the part in silver or gold, and offer it to her, and they sacrifice sheep (alpacas) before this image at certain times.” (Relacion de los primeros descubrimientos de Francisco Pizarro y Diego de Almagra (1526), in Currie, 1994)

[Image, above left: Quimbaya, Colombia. More on Ecuador. Watch this space for additions on Peru.]

Venezuela and the Guyanas

Everything sprang from Kuma, and everything that the Yaruro do was arranged so by her—the other gods and culture heroes act according to her laws.—Anonymous Yaruro person, circa 1937

In Venezuela, the matrilineal Yaruro of the Rio Capanaparo venerate Kuma. She created the world with the help of two brothers, the water serpent Puaná and the jaguar Itciai, after whom the social moieties are named. Kuma lives in a western paradise which the shamans see in visions, and to which they make spirit journeys. She is depicted with upraised arms on the shaman’s rattle. A pole is set up around which “men and women dance in separate circles.” (Zerries, 252-3)

In the Orinoco delta, the Warao say the forest is a tribe of trees, bushes, and palms. The red cachicamo tree is Dauarani, the Mother of the Forest, and its guardian. Anyone who wants to fell a tree to make a canoe must seek her permission, and the consent of her daughter, the tree. Shamans ritually approach the tree-woman, who appears as a maiden wearing a comb and beaded necklace, and sing to her. The canoe carved from her wood is vulva-shaped, and the Warao, who call themselves Canoe People, compare its cargo to the fruits created by the Mother of the Forest. (Halifax, 144-5)

Along the coast of Surinam, the Cariña Caribs revere Amaná, a self-conceiving Mother whose essence is time. They say that she was never born, that she exists eternally. Amaná has borne all beings and can take any shape. She lives in the watery Pleiades in the form of a woman-serpent, renewing herself continually by sloughing off her skin. They call her a sun serpent, and another name for her is Wala Yumu, “spirit of the kinds.” She especially rules all water spirits. The Cariña call powerful rocks at the rivers’ headwaters Mothers. Shamans commune with these beings and with Amaná for visions and healing.

Like many other divine women of the Americas, Amaná bore twin brothers. Tamusi, ancestor of the Cariña,

was born at dawn, and moonlight is sacred to him. Yolokan Tamulu, “grandfather of nature spirits” was born at dusk and has to do with darkness. These twins are complementary powers, but Tamusi is more closely associated with Amaná and her Pleides constellation. (Zerries, 245-7)

The Cariñas have a saying: “If there were no spirit to cause everything to be as it is, there would be nothing.” In their philosophy, spirit precedes matter: “We believe that the aula [word, speech] of every wala [species] has existed from the very beginning, and that it created the physical aspect. Every wala in the visible world is the physical counterpart of a flowing wala [melody] which gives it life. The sound which a creature makes is the expression of its vital principle.” For the Cariña, every “kind” has its “boss” spirits. The Arawakans have a similar concept and “use either the suffix oyo (‘mother’) or kuyu or kuyuha (‘wildness or shyness of an animal’).” (Zerries, 267-9)

In the beginning Amana rode a wave which was the milky way. She is also described as riding a turtle. She created the sun for warmth but did not anticipate how hot it would be, and it burned the moon. She has to keep immersing the sun in the ocean to protect the earth from its scorching rays. Her two sons help her fight its heat. During the day, Tamusi cuts away sun ray serpents and casts them into space. At night Tamula covers the sun with layers of darkness. (www.godchecker.com/pantheon/south_american-mytholog.php?deity=AMANA)

In the origin story of the Caribs, a Warrau man warned his sister not to bathe at a pond when she was in her courses. But she disregarded him and was captured by the great water-snake Uamma. She then conceived. Her brother got suspicious when he saw her bring home large amounts of bullet-tree seeds, without ever taking an axe to harvest them. Spying on her, he saw the Uamma snake come out of her vagina, climb a tree, and shake it so that the seeds fell down. Then the snake slithered down and went back into her body. The brother brought helpers the next day to kill the serpent. They struck as he was descending the tree and chopped him to pieces. In grief the woman collected all the pieces, which each grew into a Carib person. This new people lived in harmony with the Warraus, exchanging gifts of food. The snake’s wife, now a very old woman, still wanted revenge for the snake’s slaying, and told the Caribs to kill a child sent to them with food. This sparked a blood feud, and the Caribs prevailed. In the Warrau version of this story, the ending is peaceful, with friendship and paiwarri drinking. (Roth, online)

The Arawaks of Guyana told of a creator pair: the male Kururumany formed men, and the female Kulimina formed women. After these people populated the land, they fell into corruption, and so death was decreed for them. Kulimina may have been the sister of the masculine creator, since he is described as having two wives, Wurekaddo (“She who works in the dark”) and Emisiwaddo (“She who bores through the earth”). The second name refers to the cushi ant, a red ant that burrows in the earth. (Alexander, 259; Roth, online)

Traditions of the Amazon basin may provide a clue to the ant’s significance. The Kayapó say that the little red ant is the relative of manioc and guardian of the women’s fields. She keeps the bean vines from choking the manioc by chewing through them. So Kayapó women often paint their faces with the ant pattern. (Nimuendaju, online)

Mothers of Manioc, Mothers of Animals

Many rainforest peoples hold ceremony to honor the Manioc Mothers, and invoke her like the Mundurucú shamans in Brazil: “Mother of manioc, show favor to us. Let us suffer no famine; we call on you each year with our prayers. We have not forgotten you.” (Zerries, 276)

In Ecuador, the Canelos Quichua honor Ningui, who is the soil of their fields, the chagra mama “Garden Mother.” She is also Mother of clay and ceramics, and the very spirit of culture.

For the Shuar (“Jivaro”) of eastern Ecuador, Ningui is the Earth Mother. She taught Shuar women agriculture in ancient times. After planting their crops, Shuar women hold dances and ceremonies for five nights to honor Ningui, asking her to make their manioc grow. They also call on her in tobacco feasts which women hold for each other, to give young women strength after their first menses and to reinvigorate older women. They plant manioc during these ceremonies, chanting incantations over the cuttings. (Zerries, 277)The women call on Ningui through the nantára, a stone of unusual shape which contains the female soul of the manioc. They paint the first manioc cutting red, and the honoree places it against her vulva. All the women planting manioc sits on a tuber. Once they have finished planting, they place a ceremonial digging stick into the ground, dance, and pray to Ningui.

The Witoto celebrate the Okima festival to honor the manioc spirit and ancestors with dancing and stamping tubes, flutes and torches. In this ceremony “the women mimic the gait of the moon woman as she leans on her staff made of a food plant ‘like ñame (yam)’.” The Witoto say that manioc began with a girl called Dark or Blind who conceived by a spirit. She gives birth into a pot and doesn’t look at the child. When she returns some time later, a manioc tree is growing there. (Zerries, 278)

The Manioc Mother belongs to a broader spectrum of guardian spirits. Every kind of animal has its “mother” who nurtures and protects it. The Camayura of Brazil call them mama’é. Manioc has three Mothers, who are represented by posts representing the tools of manioc farming, as well as the fishy mama’é who gave the people manioc and farming technology long ago. (Zerries 279-80)

The sacred female in Brazilian archaeology

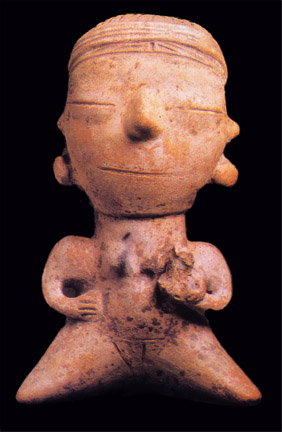

Female icons in terracotta appear in large numbers at sites along the Amazon river, especially the Tapajós region, Santarem, and the Marajó island where the river empties into the south Atlantic. Large clay sculptures over a meter tall are also known from the Amazon region.

Two sets of small figurines from the Tapajós river valley

A blissfull woman in the triangular-legs pattern typical of Santarem, and parts north as far as the Caribbean islands.

An owl-faced urn from the Amazon river,

adorned with coursing spirals.

Among the Tupí peoples of Brazil, the title Cy (“mother”) addresses female spirits of land, water, and heavenly bodies. In the 1750s, the missionary João Daniel wrote about sacred stones in a forest sanctuary, which the Portuguese destroyed. He said the sun was venerated as Coara Cy, “mother of day,” and the moon as Ja Cy, “mother of fruits.” People celebrated when the new moon appeared. “These two heavenly bodies were regarded as divinities, creators.” (Palmatary, 15-16)

For the Mundurucú, Putch ˆSi (“mother of game”) is a power who lives in upland springs where rivers originate. She roars when she moves, and the animals follow her. She appears in the form of a tortoise or coatá monkey, as well as in stone wirakuá. Shamans keep tortoises as her avatars, feeding them möri paste of manioc and scented water in order to propitiate Putch ˆSi. The most gifted shamans made shamanic journeys to visit her manifestations, making offerings and calling her so that hunting would go well. The Game Mother kills those who break her law by eating her special animals, disrespecting animals they kill, or wasting their flesh. (Zerries, 260-1)

The Mundurucú also propitiate Asima ˆSi, “the mother of fish” who rides on an alligator and is the guardian of all aquatic animals, including mammals.(Zerries, 265) In Ecuador, the Canelo say that a certain kind of tick attracts game, and bring it on hunts. They call this tick Aischa mama, “mother of game.” (Zerries, 262)

Women, Serpents, and the Waters

A widespread South American theme connects divine women to sacred lakes and serpents. The Chibcha culture-giver Bachué comes from the lake as a woman and returns as a snake. The Caribs say they are descended from a woman who carried a water-snake in her vagina. The Venezuelan goddess Maria Lionza is either carried off by a serpent or becomes one when she gazes into a lake (see below). Brazilians speak of the water-mother (mae d’agoa) and Peruvians about the Yacumama, a river spirit who is a two-headed serpent.

Sacred lakes also figure in Brazilian legends about amazons called Icamiabas. Many indigenous peoples of the Amazon had traditions about the Women-Living-Alone, the Women-Without-Husbands, the Masterful-Women. (Alexander b, 285) The Waurá of the Xingu river still celebrate rituals in their memory. (Schultz, 142) The great Amazon river is named after the women warriors encountered by Spanish soldier Orellana. The chief Aparia asked him whether he had seen the amazons, “whom in his language they call Coniapuyara, meaning Great Ladies.” (Van Heuval, 117) This name could be rendered as “masterful women.” (Spruce, 457) Other sources translate it as “Great Lord” (Alexander, 285, among others) or as “mighty chieftains”—but they ignore the meaning of conia (cunha), “the Tupí word for woman.” (Southey, 86) The “mighty women” title, like the Waurá ritual and similar traditions, suggest a supernatural status for the Coniapuyara / Icamiabas.

A very widespread Tupí tradition says that there is a sacred lake near the source of the Nhamundá (Jamundá) river. It is called Yaci-uaruá, “mirror of the moon.” Every year the Icamiabas hold a

ceremony to honor the moon and the Mother of the Muiraquitãs who lives in the lake. The women purify themselves, and when the moon shines on the waters, they plunge deep into the lake to receive muiraquitãs from the goddess. These are jade amulets, often in the form of frogs, and also fish, tortoises, and other shapes. By some accounts, the Icamiabas scooped up clay from the lake bed and shaped it into these forms. Once exposed to air or moonlight, the muiraquitãs hardened into stone. Another version holds that the Icamiabas caught little underwater animals and froze their forms by dropping a little of their own blood onto them. (Palmatary, 75)

These “greenstones” or “amazon stones” were sacred and highly valued, worn and gifted and traded as far north as the Carib country. Early colonial reports place the muiraquitãs around the Nhamunda and Tapajos rivers. Many sources refer to their healing properties. In 1851 the traveler Castlenau related that “The Indians attribute to them the greatest medicinal powers.” Tapajós women used them to prevent disease and to conceive. Nursing mothers preferred pale and yellowish stones which were said to increase the flow of milk. (Palmatary, 79-80) In Guyana they were often worn by chiefly women, as Sir Walter Raleigh remarked: “…commonly every king or cacique hath one, which their wives for the most part wear; and they esteem them as great jewels.” (Raleigh, 202; emphasis added) Centuries later, Fernando Sampaio called the muiraquitã “a symbol of feminine power.” (de Camaris, online)

In southern Brazil, the Paressí creation story begins with the stone woman Maisö, when earth and water and light did not yet exist. She placed a piece of wood in her vagina, causing the muddy river Cuyaba to pour forth, followed by the clear waters of the Paressí. Then Maisö created the earth by putting land in the rivers, and gave birth to many stone people. Among them were the couple Darukavaitere and Uarahiulu, who procreated the sun, moon, and stars and placed them in the heavens. They also brought forth parrots and snakes and the first human Uazale, ancestor of the Paressí. (Lowie, 172)

Guaraní Cosmology

There are several versions of the creation story by the various Guarani peoples. Many accounts feature a sole masculine creator, perhaps under Christian missionary influence, but others say that creation was a joint effort of Tupã the sun and Arasy the moon. They descended to earth, to the hill Arigua, where they created seas and river, woods, stars, and all the beings of the universe. They formed humans from clay mixed with various natural elixirs and water, both making a statue in their own likeness. The people came to life with the sun’s rays, and sat before their creators who named them.

Arasy spoke first, and when the humans replied, it was again the woman Sypavê who spoke first. Tupã told both to love each other and have many children, take care of them, and that they’d have everything they needed. Arasy interrupted, saying that people need to work, or their life would be a slow death. So Tupã agreed. They instructed the first people on how to live, to avoid unnecessary harm to living things and to tattoo their faces to remind them of the sacred. They told them that Earth is their mother and the Moon is her sister. (Colmán, online)

The Tavyterã speak of an earlier divine generation, Our Great Grandfather who suckled himself and raised his wife out of his ceremonial crown. This was Ñande Jari Jusu, Our Great Grandmother, Great Golden Flaming Ritual Staff. The two quarreled, and Grandfather decided to leave the earth. In his anger he wanted to destroy the earth, but Ñande Jari succeeded in protecting it by singing the first sacred song, to the beat of the takuára (women’s ceremonial staff). (Grünberg, 4)

Another Guarani story says that a great flood destroyed the previous world, but the ancient grandmother Chary Piré survived through her shamanic power. “As the floodwaters rose, Chary Piré stamped out a dance beat with her rhythm stick and sang a powerful chant without stopping.” She caused a palm to grow between heaven and earth, and took refuge at its top with her son. (Sullivan, 187)

As the divine Grandparents had quarreled, their children had a similar disagreement, and Our Father left Our Mother, Ñandecy. (Grünberg, 4) Some stories say they fought over her having made love with another. In one version, Ñandecy could not believe that the corn her husband sowed had ripened immediately. Annoyed, she told him that another man had fathered the child she was suckling, and he left. Later she and her child went looking for him on the path of tigers.

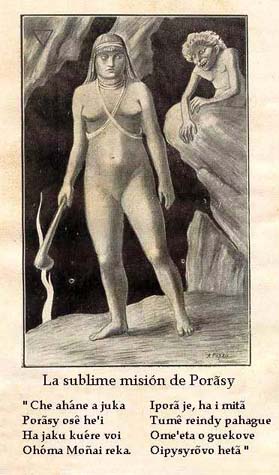

The Tiger Grandmother gave them shelter and hid them from her grandchildren. But the young tigers found and killed Ñandecy. Later her son with his magical twin avenged her death by killing the tigers. [Colman, online] This theme of a divine woman who has twin sons and then dies is a common theme in stories across the Americas. The Guyana Caribs tell a very similar story about a mother slain by the tiger and avenged by her twin sons. (Roth, online)(Right: Porãsy, daughter of the divine grandparents, sacrificed herself to destroy the seven monsters sired by Tau. The text is Guaraní, a living native language.)

Ñandecy went to the world of the ancestors, and rules the land-without-evil, in the waters to the east. A parrot meets all comers with food and judges them; only the humble can enter. While the male creator has withdrawn far away, Ñandecy cares about humans. Thus she became the focus of Guaraní millennial movements after the European conquest. (Zerries, 241)

The Sun and Other Sky Women

The Toba people in northern Argentina say that the sun woman Aquehua lives in the heavens with other star women. She weaves a ladder of her hair so the jaguar man can reach her in heaven. She becomes whitehaired and old, but is annually renewed by this encounter. Or, in another version, she does battle with the jaguar who is trying to eat her. (Monahan 1994, 192)

The matrilineal Tobas say that in the beginning women lived in the sky and the stars were their houses. Men lived as half-animals on the earth below. One day the sky women decided to go down to earth to look around and taste its fruits. They descended by long cords many times. Once while the men were out hunting, the women came to their hut and ate all their food. The men couldn’t figure out what had happened, so they set someone to keep watch. The rabbit-man fell asleep and didn’t see what happened. The parrot-man saw how the women came down from the sky, but one of them threw a stone and broke his beak, so he was unable to tell what he saw. The eagle-man was stunned by the brilliance created by the cord brushing against the earth and his speech was too confused to understand. Then the bird-man stood guard, and when he saw the women descending, he flew and cut the cords, trapping those who had landed.

The men were attracted to the sky-women and wanted to have sex with them. The fox man grabbed the prettiest and carried her to his hut, but soon came out screaming and holding his crotch. He said the woman had bitten him with the teeth in her vulva. The men saw that the women used these lower teeth to chew their fruit. The bird-man invited the women to sit crosslegged on the ground in a circle. Then the men built a fire and danced hard all night, beating the ground with their feet and making the ground vibrate. At dawn they collapsed in exhaustion. The women got up and went over to them, but the teeth remained stuck in the ground where they had sat. Then men and women got together and had human children.

As for the women who remained in the sky, the sun woman Aquehua stayed close to the earth near her sisters. Sometimes she moves quickly, like a young person, which makes the days short and cool. Other times she goes slowly like an old woman, and the days are long and hot. She regenerates herself, turning from young to old and then young again, and will until the end of time. (Bernardo, online)

Among the star women of the Toba are “three old women who live in a large house with a garden.” They are the stars in Orion also known as the Tres Marias. Star Woman (the planet Venus) produces the Magellanic Clouds by pounding carob into flour in her heavenly mortar. (Metraux, 365)

The Goddess Appropriated

Stories of men seizing the sacred ceremonies, instruments, and masks from women are widespread in South America. The Yamana of Tierra del Fuego say that Húanaxu was the leader of women, who once ruled. Men killed all the women in a patriarchal coup. Furious, Húanaxu rose into the sky as the Moon, and sent a great flood to punish the slaughter. (Monaghan, 2009)

The Selk’nam too said that the moon, Kreeh, was a powerful shaman who led the women’s ceremonies and decided who would play which spirits. Among them was the chthonic serpent Xalpen who arose from deep in the earth, causing the ceremonial hut to shake and flames to spit forth. But the men found out and overthrew the women, and Moon became a despised figure, though her power was yet feared. (Chapman, 67-73)

In Venezuela, the Arawakan Wakuénai tell of how Amáru and her women take the sacred flutes away from her trickster brother and the men. This act opens up the world after an earlier destruction, and the women play the flutes as they travel through the valleys of the Orinoco, Vaupés, Negro, and Amazon rivers. The trickster tracks Amáru down at a lake, but she escapes through a secret underground passage and returns to the mythic center. Finally the men reestablish control over the sacred flutes, tricking Amáru into thinking that the instruments have turned into wild animals and birds. They use the colonial lingua geral (a mix of Tupí and Portuguese) to accomplish this deceit. Yet Amáru retains great power; she is “strongly associated with the eastern horizon, the sun’s heat as it rises to light up the day, and the biological power of fertility and giving birth.” (Hill, 237-40)

In the Gran Chaco, the Ishir (Chamacoco) say that the male overthrow went so far as to actually kill the ajnábsero (spirits). Only the great goddess Aishnawerhta or Ashnuwerta regenerates herself. She is the most powerful of the ajnábsero, and for humans she is the Great Teacher, the Giver of Words, who reveals the law and brings culture. She protects the land and animals by regulating hunters and food distribution. She is Ashnuwerta of the Red Splendor, of the Black Brilliance, Mistress of Water and Fire, Mother of the Birds of the Benign Rain, Mistress of the Dark Blue Storm. (Escobar, 40-1, 55, 30-33) Her name can be translated as “Lightning, Brilliance,” also as “Flower, Intensely Red.” She is all-knowing, present everywhere, and beyond time. (Cordeu, 268-70)

Ashnuwerhta, painted by Ishir artist Basybuky (Claudelino Balbuena)

Then how could she be killed? The men’s tradition says that it was done at her own instruction, because the women had looked down on men and tricked them. In the early days it was the women who performed the sacred rites that renewed the bonds between all beings. Once men had learned the ways of the ajnábsero, their calls and movements, they did not need them and wanted to get rid of them. Inexplicably, Ashnuwerta revealed to the chief (her lover in the story) how to kill the ajnábsero, herself included, by striking the mouths hidden in the fur on their left ankles. (Escobar, 30-5; Cordeu, 268)

The overthrow of the women began with the men seizing boys and subjecting them to severe tests in the initiation house. Some boys died, the chief’s son among them. Then he vowed revenge on the spirits. With Ashnuwerta’s help, the men killed the ajnábsero. Some versions say the men were only going to kill some of them, but got carried away and murdered the helping spirits too, ignoring the goddess’ pleas to stop. Then Ashnuwerta told the men that they must take the ceremonial places of the ajnábsero. She made it so that each slayer acquired the clan identity and symbols of the spirit he killed. She taught them each their costumes, paints, dances and rites. The protectors of these clans were (still) ancestral females: the Jaguar Mother, the Monkey Mother, and so on. (Escobar, 36-50; Cordeu, 268)

The story says that it was Ashnuwerta who imposed the Great Secret: women were to be kept ignorant that the dancing ajnábsero were really their men. But the women rejected the fiction at first: “Doubled over with laughter, they ridiculed the actors, mocking their attempt to supplant the gods.” Then they discovered the murders. While searching for honey in the forests (a delicacy they hid from the men) the women came across the rotting bodies of the ajnábsero and mourned their deaths. But back in camp, they concealed their knowledge of the killings, making excuses for their red and tearstained faces. (Escobar, 53)

But the men followed the women and found out that they were gorging on honey and mourning for the spirits. They complained to Ashnuwerta who, so the story says, instructed them to kill all the women. She promised they would be resurrected and would remember nothing. The men were only to spare Ashnuwerta. So the slaughter began (girls too) and again men ignored the goddess’s instructions. One man came after her with a club, but she turned into a doe and escaped into the forest. They found her again as a woman sitting in a tree. She had sex with all the men, then instructed them to kill her. Each man was to take a piece of her body and wait til night when the women would rise again from her own flesh.

The women were not the same. Some were bigger or smaller, because the dismembered flesh of the goddess had been shared out unequally. Those made only from the blood of the goddess were like “faded copies of themselves.” Most importantly, their memories had been erased, and they knew nothing. Since then, the women believe that the men in ritual costumes are really the ajnábsero, or so they say. It was said that a curse would fall on the Ishir when the men forget to imitate the gods and the women stop believing that they are. (Escobar, 60-1; Cordeu, 271) What the women really thought of all this is never told, though there is evidence in the parallel case of Tierra del Fuego that the Selk’nam women were aware of the “secret.” (Chapman, 74-5) As for Ashnuwerta, although her body was cut up and reincarnated as Ishir women, her immortal and eternal being lives on in the Milky Way with the “invincible shamanic souls.” (Escobar, 30)

Maria Lionza

In Venezuela, a thriving modern tradition has coalesced around the goddess María Lionza. Her name was originally María de la Onza (of the tapir). A bronze statue shows her as a wildwoman riding this quintessentially South American animal at the entrance to Caracas. María Lionza reigns over the wild animals, a benevolent goddess of nature, love, and peace. She lives in a palace on Mount Sorte, by the headwaters of the Yaracuy river. She is enthroned with snakes and turtles, and flanked by lions and goats. Her devotees make a annual pilgrimage on October 12 to be purified in her spring, make offerings to the waters, and trance-dance over red-hot coals. (Mervin and Prunhuber, 61; Andrade, online)

Her origins are Indian but African and European strands are blended into her veneration. They say she was the daughter of a Caquetío or Jirjana chief in the Yaracuy. Beyond this, the story branches out in many directions. Her green eyes were taken as a dangerous sign, so her father threw her into the lake for the anaconda. She immediately reemerged as a goddess surrounded by animals, plants, and waters. Or, a prophecy warned against the birth of a green-eyed girl: if she ever saw her reflection in the lake, a giant snake would come out of her and cause destruction. She was to be sacrificed to the anaconda of the lake, but her father hid her away. One day her guardians fell asleep and she started exploring. When she saw herself in the lake, she turned into a snake and began to expand until her body burst, releasing a flood. Her head stayed in Acarigua, and her tail in Valencia. Or, the anaconda of the lake carried her off. He was punished by swelling up and bursting, again causing a flood. María Lionza then became mistress of the waters and fish, and finally of all the surrounding lands. (Mervin and Prunhuber, 61)

In a version recorded by Homero Salazar, her dazzling green eyes were a good omen for the Caquetío, then suffering under the Spanish conquest. She was called Yara, and her mother Tupi took her to a mountain refuge. She became a diplomat in talks with the Spanish, but they refused to make a treaty, so she returned to the mountains. (Andrade, online) The modern priestess Veit-Tané says that Maria Lionza was chosen to be a priestess for her spiritual powers. When the Spanish invaded, she fled to the mountains and tried to rouse her people to resist. They called her a witch, but she used her divine power to help them anyway. he helped them anyway. The missionaries recast her as the Virgin Mary, baptizing her as Maria de la Onza. (Mervin and Prunhuber, 61)

In the 1920s new stories make the goddess over as a white woman who vanished while swimming in a lake, and was rescued by a boar (onza), her double. Or, Maria Concepción de Sorte was born to a Spanish family but grew up among the forest animals. She ascended to the heavens, where the Indians made her queen, and she rode on a boar.

The worship of this syncretic goddess incorporates Ave Marias, spirit mediums, and the Seven African Powers of Yoruba-based santería from Cuba, as well as Haitian influences. She heads a Venezuelan Trinity with the Indian resistance leader Guaicapuro, and Black Felipe, a Cuban who joined the Venezuelan revolution. She is surrounded by spirit courts composed of river and mountain spirits, saints, and historical figures such as Simon Bolívar. She has Indian, African, Hindu and Arab courts, medical and political courts, and a court of Venezuelan folk characters. Andrade and other scholars describes her religion as “horizontal” and participatory, with lots of gift-giving.

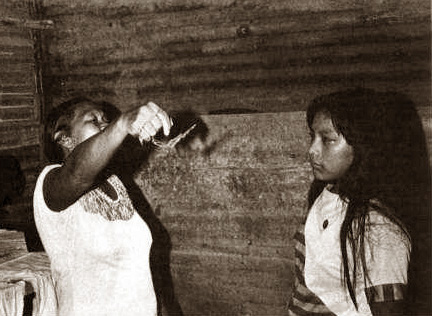

An Arawakan curandera in the tradition of María Lionza, VenezuelaThe statue of Maria Lionza cracked just before the fall of dictator Marcos Perez Jimenez. More recently it broke in half, which some see as an omen for Hugo Chavez, who is rumored to be a believer in the goddess. [“The goddess and the president” by Mike Ceaser, BBC News, June 22, 2004]

Old Spider

Spider Woman shows up in ancient Nazca pottery and weaving in southern Peru. Several traditions identify Spider as the moon. The Witoto say that the highest heaven belongs to her, and the Paressí say that the new moon crescent is a spider covering the orb. (Johnson, 213)

The Mapuche say that Lalén Kuzé, Old Spider, taught a girl abducted by an old man to spin. He had demanded that she finish working a huge pile of wool by the time he returned. She was crying by the fireplace when Choñoiwe Kuze, Old Woman Fire, spoke to her and told her not to be upset. “I’ll call the Lalén Kuzé to help you.” And Old Spider soon came crawling down the chimney. She taught the girl and finished the task. [www.beingindigenous.org/regions/mapuche/art_ma-tex1.htm Jan. 3 2009]

Copyleft by Max Dashu. May be reproduced with attribution.