Maps Copyleft 2006 Max Dashu

(May be fair-used with attribution)

Matrix Cultures

Catalog

Bookings

Exodus of the Zigula (“Somali Bantu”)

Max Dashu, Suppressed Histories Archives

Many scholars think that the ancestral Bantu cultures were matrilineal. Even today some cultures retain mother-right traditions, in the “matrilineal Bantu belt" of south-central Africa. (The term Bantu means, loosely "the people," like so many aboriginal names, putting a humanizing prefix before the being-radical Ntu; it long predates the racist usage of the apartheid government in South Africa.)A little-known historical pocket from this cultural line was forcibly transported into northeastern Africa. Omani slave-traders based in the Sultanate of Zanzibar carried off people from Tanzania, Mozambique, and Malawi, and shipped many of them for sale in the slave markets of Somalia. Tens of thousands of these southern Africans ended up laboring on plantations in south Somalia.

The major groups are the Zigula (or Zigua) and Shanbara. Zigula oral history says they escaped slavery as a group and thus preserved their language. They scorn the Shanbara who no longer speak a Bantu language, only accented Somali. This group claims descent from “five original brothers who belonged to east African groups such as the Yao, Makua, Nyasa, Nyamwesi and others.” [Declich: online] They became farmers of the Juba and Shebeli rivers in Somalia: Shabelle, Shidle, Makanne, Eyle, Elay Baydabo.

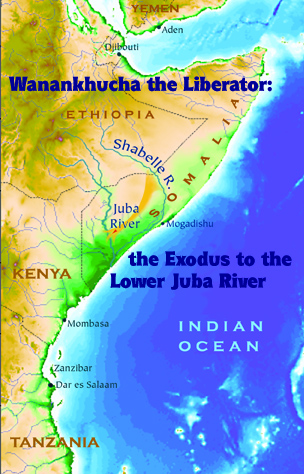

The great hero of Zigula oral history is Wanankhucha, a mganga diviner and prophetess. She organized the escape of large numbers of Zigula people from slavery and led them to freedom in the mid-1800s. They say that her visions and power as a diviner enabled her to guide her fleeing people out of danger. She is also credited with building unity of the emancipated people by “organising repeated performances of traditional Zigula songs.” Their goal was to return to Tanzania, but Wanankhucha's group of refugees faced great dangers in their migration, including the possibility of being reenslaved on their way through Kenya. So they settled in the lower Juba valley in southern Somalia, after Wanankhucha decided that an earthquake there was a sign. [Declich: Online]

The so-called Bantu Somali were conquered by the Oromo and later by Somali pastoralists. Some Zigula farmers adopted pastoral people who intruded on their country, after a period of clashes. There were also foragers called Bon, and various low-caste groups, either despised professions or descendants of slaves. The slaves often lost their original family names, and were left with slaveholder’s names.

The pattern was pastoralists styled as nobles, and farmers as slaves or ex-slaves, so that all farmers came to be considered “freed slaves.” All the non-elite groups got lumped together as Bantu. Italian colonialists reinforced this categorization and deepened it by forced labor conscription to their plantations, such as the Bertello farming contract. They refused to accept ethnic distinctions, outside of “pure Somalis.” “You are all Mushunguli Mayasid (Bantu).” (from a word meaning Zigula person) The Italians enlisted Somali pastoralists to round up people from farming groups to perform forced labor.

Colonization was heaped upon colonization, because the Italians also used gender divisions to defuse “Bantu” men’s resistance to their own exploitation as members of oppressed ethnic groups. “Men to be conscripted into forced labor were given the right to choose any woman they wanted as a wife, without her consent or that of her relatives.” These men were freed from the obligation to pay bridewealth for the non-consensual wives, and fathers were threatened with conscription, for themselves or their sons, unless they surrendered their daughters. This strategy seems to have been effective, since, as people from the Juba region told Francesca Declich, “without the company of a woman most young men would have run away from conscription.” [Declich, online]